Tomasz Stanisław Sikorski was born on 19 May 1939 in Warsaw as the second child of Kazimierz Wincenty Miłosz Sikorski and Helena Julia née Froelich. His father was a notable composer and an experienced teacher, as well as a very active organiser of musical life in inter-war Poland. Sikorski’s mother came from a wealthy family of Łódź industrialists. She was Kazimierz’s student in the 1920s, but did not finish her studies at the conservatory. Thus Tomasz inherited his musical talent from both his father and mother. His sister Ewa, two years his elder, was also musically talented.

Helena never worked professionally – she devoted herself to her family and to bringing up her children. In addition, she took over all domestic chores, because Kazimierz Sikorski simply had too many other things on his mind. His involvement in family life was also limited by his numerous professional duties. As a result, the children grew up more beside their father rather than with him. Another reason may have also been Kazimierz’s age – when his first child was born, he was already over forty.

The atmosphere at this intellectual home was conducive to the children’s versatile development. However, this was by no means an ‘open house’, often full of guests, where a lot was happening. Kazimierz Sikorski was not a highly sociable man. He was rather shy, distanced and formal, warm but not eager to fraternise.

Home was a family enclave where the children were to feel safe and where they would have optimum conditions for learning and resting. Until year 8 young Tomek was educated by means of private lessons – neither he nor his sister attended any school. This had a big impact on shaping the children’s personalities. As Ewa Sikorska recalls:

As children, we were cocooned and that is why we remained immature for a long time. Tomek’s umbilical chord was never cut. His health was poor, he had an organic heart disease and untypical infantile rheumatism.

After the war the Sikorskis moved with their children to Łódź, where Tomasz’s father served first as Dean of Faculty I (of Theory, Composition and Conducting) and from 1947 as Rector of the local State School of Music. The family moved to a flat near the school, at ul. 1 Maja 3.

In Łódź, when he turned nine, Tomek began regular piano lessons with Helena Ilcewicz. There is no doubt that already at that time he displayed considerable proficiency in playing the instrument – at least for his age, if just three years later he was ready for his serious pianistic debut. In 1951, at the age of merely twelve, Tomasz Sikorski performed Joseph Haydn’s Concerto in D major with the Łódź Philharmonic Orchestra. In subsequent years he performed two more large works with the same orchestra: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Concerto in A major (in 1952) and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Concerto in C major (in 1953).

In September 1954 the Sikorski family returned to Warsaw. Kazimierz Sikorski was transferred to the State School of Music in Warsaw, where he had been teaching already since 1951. He was succeeded as Rector in Łódź by Mieczysław Drobner. Kazimierz Sikorski was his counterpart in Warsaw in 1957-1966. The Sikorskis moved to the writer Maria Dąbrowska’s old flat at ul. Polna 40. Shortly after the move, on 1 October, Helena Sikorska died in a tragic accident under the wheels of a tram. For her teenage children, so attached to her, this was a huge blow. Her death also deeply affected Kazimierz Sikorski, who became even more withdrawn and very taciturn. He must have felt lost in the new situation, having now become responsible for all the domestic and family chores.

In Warsaw Tomasz and Ewa Sikorski continued their musical education at the State Secondary School of Music at ul. Myśliwiecka 14. Their school friends included many talented young musicians, e.g. Elżbieta Chojnacka and Jerzy Maksymiuk.

The time spent in the secondary school was also the time of Tomasz Sikorski’s first serious attempts at composition. Although – as Zygmunt Krauze recalls – Tomasz had thought seriously about composing already in Łódź. This was when he became fascinated with echo and already started working on pieces inspired by this phenomenon.

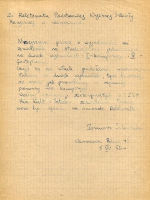

14 June 1956, less than a month after his seventeenth birthday, Tomasz Sikorski passed his graduation exam in piano and received his secondary school leaving certificate. That he was a rather diligent pupil can be seen in the numerous very good marks he received. He got them in all musical subjects (ear training, musical principles, general harmony, Polish musical folklore, counterpoint, instrument studies, musical forms and history of music), except – surprisingly – for his main subject (piano), in which he got a good mark, as well as many general subjects: German, history, geography, psychology, physics and chemistry. His marks in the remaining subjects were good and his behaviour was marked very good. Owing to his health problems, he was exempted from physical education classes.

Even before taking his final exams, Tomasz Sikorski had already decided without hesitation what he would do next. In mid-May 1956 he submitted an application for admission to the State School of Music in Warsaw to study composition and piano.

He took his entrance exams on 6 July. His chosen topic for the exam paper was: ‘The significance of the music of Chopin, Moniuszko and Szymanowski to the development of Polish music’. His paper was marked good (4). The review reads as follows:

Chopin’s and Szymanowski’s oeuvres approached in an interesting manner; the author is right in pointing to analogies and contrasts when discussing these two composers. The mark could have been v. good, if it had not been for the author’s perfunctory analysis of Moniuszko. His aversion to this music does not entitle him to disregard Moniuszko’s historic role almost completely.

The aversion mentioned by the reviewer probably appeared suddenly and may have been caused by problems with a running out pen, which must have unnerved Sikorski, who was in any case nervous by nature, and problems with time that was also running out. Trying to end his paper with a punchline and having no original idea, the composer wrote with honesty that was typical of him:

I can no longer bear listening to Moniuszko’s music.

Fortunately, this did not prevent him from fulfilling his dream of getting admitted, although he did not achieve everything he wanted, for he was not permitted to study two subjects simultaneously. Thus he began studying composition with his father, studying piano informally with Prof. Zbigniew Drzewiecki. He did not obtain permission to study the second subject officially until 1958. However, he interrupted and then resumed his piano course several times, took leaves of absence and in the end did not complete his piano studies.

This was caused not by a lack of enthusiasm for developing his pianistic skills, but by an accumulation of tasks, which occurred towards the end of his composition studies and shortly after their completion, especially in 1963. This was the time when Sikorski made his Warsaw Autumn debut with Antiphons, was hired by the School as a teacher and worked on new compositions. Thus the subject of his piano studies died a natural death – Sikorski simply did not have time for them. Formally, he had no need for them either. He saw himself as a composer in the future and he received his Master of Arts degree – as part of the first State School of Music class in Warsaw – in 1962.

For Sikorski his time as a student was not only a purely musical experience, but also a very intense time of experimentation and discoveries in various fields of art. His main companion in these ‘escapades’ was Zygmunt Krauze, with whom he had started ‘daydreaming’ already in secondary school in Łódź. The boys together discovered various literary, poetic, painting and musical works; they inspired and ‘infected’ each other with what was new and fascinating to them. Thus they expanded their horizons and, above all, constructed their artistic worlds.

In addition, they had access to the latest music, both in the form of recordings and scores. There were several sources: Nadia Boulanger – a friend of Kazimierz Sikorski, Marceli Stark – a professor of mathematics and expert music lover, Zygmunt Krauze’s brother, who had gone to the United States to write his doctorate and who regularly sent recordings from there, and John Tilbury, who in 1961 came to Warsaw to study with Zbigniew Drzewiecki. He, too, could bring new material from behind the iron curtain fairly easily.

It was when he was in secondary school and then when he was a student that Tomasz Sikorski started most of his friendships – honest and unconditional friendships, which, even when not ‘cultivated’ for years for a variety of reasons, lasted till the end of the composer’s life. Sikorski’s closest friends included, in addition to Krauze and Tilbury, also Zbigniew Rudziński – four years his senior, but who began his composition studies in 1956 as well. They spent so much time together that at some point they began to be referred to as ‘inseparable’. The older friend was extraordinarily understanding and patient. While he was with him, Tomek could behave without any reserve. Towards the end of their studies the two friends, together with John Tilbury (and then also with Zygmunt Krauze), began to organise concerts of 20th century and contemporary music at the Polish Radio. These concerts became the basis for the ‘Warsztat Muzyczny’ ensemble.

As a student, Tomasz Sikorski worked very intensely on developing his artistic skills. Studying with Kazimierz Sikorski meant he would go through the traditional course in counterpoint, instrumentation and harmony. His career as a composer was taking off. In October 1957 (after completing his second year of studies) Tomasz Sikorski was admitted to the Youth Club at the Polish Composers’ Union.

When on 11 June 1962 Tomasz Sikorski graduated with honours in composition, he began his life as an adult artist. The world stood wide open.