The period around 1970 was marked by a clear turn in Tomasz Sikorski’s work. The composer focused entirely on exploring the phenomenon of sound as such. This change of viewpoint resulted in far-reaching modifications of his musical language, though we cannot say that this turn was revolutionary or resulted in a completely different direction for the composer. As we take a closer look at his sonorist works, the changes seem very natural, even obvious, undoubtedly stemming from the sensibility of the young, constantly experimenting artist.

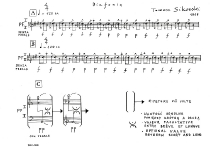

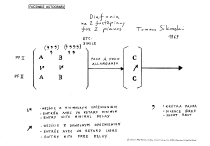

Symptoms of the new can be found already in his Sonant for piano, on which the composer began to work when he was still in Paris, in late 1965. In this piece Sikorski still treats sound as purely physical matter. He plays with resonance (catching the fading sound of the strings with the piano pedal at the very last moment) and – as he writes in the Warsaw Autumn programme booklet – his aim is to break the sound matter into ‘two layers: attack and sustain’. Something similar happens in Diaphony for two pianos written in 1969: the composer listens to newly produced sound resulting from asynchronous playing of the same melody on both instruments.

Tomasz Sikorski must have realised that by just listening to the sound matter, no matter how fascinating and exceptional, he would not be able to write outstanding compositions. Works produced in this way could at best be ‘good’ or ‘interesting’. Sikorski needed an intellectual and firm foundation for his music, a foundation thanks to which he would be able to direct the listener to the essence of sound – its expressive depth. He, therefore, made use of what was very close to him: literature, literature and poetry. Holzwege for orchestra and Absent-Minded Window-Gazing for piano are his first compositions with literary titles and some of his most highly valued works. They crown his search, in them the composer discovers a new artistic mode of expression, both in piano music, with which he was so familiar, and in the much more extensive orchestral field. In addition, they constitute the essence of Tomasz Sikorski’s mature style.

For Strings (1970) as well as Absent-Minded Window-Gazing (1971) and Holzwege (1972) are an important point of reference in Sikorski’s work, because for the first time his objective in transforming much reduced musical material is to transmit non-musical content. The composer also tries to use to the maximum the expressive capabilities of his musical material, creating a wide range of sounds on its basis. In subsequent works this ‘model’ undergoes various transformations. They consist mainly in increasing the number of the structural elements (modules) of a work as well as their size and, consequently the size of the work itself, and in enhancing the variety of the musical matter used by the composer. In addition, Sikorski increases his efforts to maintain the substantive unity of his works.

Later, he will write more works revealing their programme or indicating the source of their literary or philosophical inspiration. Solitude of Sounds (1975), Sickness unto Death (1976), Afar a Bird (1981), The Silence of the Sirens (1986-87), Diario 87 (1987) are all works in which the composer symbolically presents a pessimistic vision of a lonely human being – that is himself. His other compositions from that period are full of tension, anxiety, sadness and despair as well. Sikorski oeuvre will never bring any hope.

In the 1980s, especially in his music for strings, the composer proved much more open to expressing feelings – they played an increasingly important role and became increasingly intense. This was associated with literary content referring directly to emotions being brought to the fore.

Works like Strings in the Earth from 1979-80, Winter Landscape from 1982, Recitativo ed Aria from 1983 and La Notte, written one year, later are highly lyrical. Sikorski enhances here the role of melody – it appears even in chord series. It becomes a new quality in Sikorski oeuvre, hitherto absent or present in vestigial form. Each of these works has at least one section in which we are dealing with an accompanied melody (with the accompaniment often provided by a solo instrument). What is also transformed is expression – feelings are often no longer suppressed or hidden; they erupt and the listener has to face them directly. Harmony, too, changes– Sikorski limits the role of his characteristic dissonances in favour of gentler, more consonant and euphonic sounds, which begin to predominate. Another element lacking here is violent expressive changes; in addition, there are decidedly fewer dynamic contrasts – each work becomes a sort of continuum, without any significant climaxes and clear formal divisions. The composer abandons his sonic experiments and exploration of the very nature of sound in favour of precise shading in of colours by means of slight harmonic modifications and various methods of articulation. Not only is this process not made difficult, but, on the contrary, it is facilitated by Sikorski’s homogenous line-ups and condensed chord or choral textures. As a result, even the smallest change is twice as emphatic in the listener’s perception. Sikorski still uses short modules, repetitions of which constitute a mechanism shaping larger fragments of his compositions.

Sikorski’s oeuvre has come full circle, it has been filled and fulfilled. We cannot help thinking that the composer may have sensed that the death was coming. It is possible that when he said all he had to say with music, when he decided that he had reached a dead end, when he no longer felt strong enough to work on new ideas, he came to the conclusion that his existence had ceased to make sense. These are only speculations, but Sikorski may have decided to end his life just like he decided to stop composing.

Owing to its aesthetic distinctness, Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre occupies a special place in contemporary Polish music. Its specificity stems from the modest range of technical means used by the composer and from more general phenomena: attitude to time and space, to hearing laws, to literary texts and subtexts, and, above all, the composer’s extraordinary sensitivity to sound. This sensitivity seems to have no parallel among contemporary Polish composers.

This is how Sikorski’s oeuvre is described by Ewa Gosman in her book. Andrzej Chłopecki, too, stresses the composer’s extraordinary sensitivity to sonic phenomena:

What was and remained the most important element for him was sound – acoustic object with its swelling and sustain, its vibration and flavour. What mattered most was an acoustic fact, sonic gesture, resonating phenomenon. It is as if he collected these phenomena and pinned them to paper – like others do with butterflies. Sikorski’s pieces have something of clusters in them.

Martina Homma has a similar view of the composer’s approach to the musical matter:

It is not the sound event itself, not what releases it and not its function in musical progression that seems the most important element in this music but the sustain, echo of the sound, its secondary impact no longer subjected to active impulses. Hence the meditative nature of these works, not directed forward but back and because of that – more than because of specific repetitions and pauses – not developing.

Tomasz Sikorski’s solitude was not only personal solitude caused by the absence of another human being. He was lonely also in musical, aesthetic terms. As Andrzej Chłopecki writes, Sikorski’s oeuvre:

was a lonely alternative to successive stylistic tendencies in Polish music leading not only to sonorism and not only to new Romanticism, but also to early pointillism, later return to folklorism, to new tonality. Sikorski never followed anyone else’s path – and no one followed his path in Poland. Hence the ambiguity of his presence, his lonely presence in Polish music.

Sikorski’s musical loneliness was associated primarily with a lack of understanding of his oeuvre, with its incorrect, superficial interpretations. It may seem incredible, but this extremely simple (when it comes to structure) and direct (when it comes to expressing senses) music was completely wrongly decoded my most.

It turns out that the simplest way to describe the music written by Tomasz Sikorski is to describe what is missing from it – though is it really true that what is absent from it is denied, negated? Development, seeking something, tension, culmination, dramaturgy, process. Memory is unnecessary as a tool of perception: it is difficult not to understand a piece that lends itself so easily to listening.

Andrzej Chłopecki points to an important issue relating to listening to and perception of music: habit. Accustomed to some patterns, we often reject what does not conform to them, what destroys the order of our world. Undoubtedly Tomasz Sikorski’s oeuvre destroys the order of the listeners’ world, their sense of security; it causes strange discomfort. Someone once said that development began two metres from the couch. It is worth abandoning one’s comfort zone and search for the truth. Sikorski’s oeuvre reveals the whole truth about him – the composer revealed himself in it as he really was, he did not hide anything, did not embellish anything, did not justify anything, did not explain anything. He told the truth and asked questions true answers to which were often unbearable.